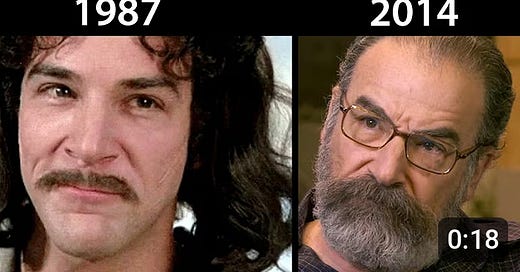

The Revenge Business: On Mandy Patinkin’s Moral Calculus

By Earl Cotten for The Earl Angle Newsletter

The room is dark, the screen flickers. A man with a sword stands over his father’s killer and speaks the line that has entered the lexicon: “I have been in the revenge business so long. Now that it’s over, I do not know what to do with the rest of my life.” Mandy Patinkin watches this scene from The Princess Bride in his living room, and finds himself weeping—not for Inigo Montoya, but for Gaza. The actor, who once channeled his grief for his cancer-stricken father into that fictional revenge quest, now sees in Israel’s bombardment of Palestinians a grotesque echo of the same self-consuming fury .

“How could it be done to you and your ancestors,” he asks, “and you turn around and you do it to someone else?” The question hangs in the air like cordite.

I. The Performance of Vengeance

Patinkin’s analogy is not literary whimsy. It is a surgical unpacking of identity corroded by retribution. Inigo Montoya’s hollow victory—the moment his life’s purpose evaporates with his enemy’s last breath—mirrors, for Patinkin, Israel’s existential trap. After Hamas killed 1,200 Israelis on October 7, 2023, Israel launched a campaign that has since killed over 58,000 Palestinians, half of them women and children, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry . The actor frames this not as self-defense but as a performance: a ritualized reenactment of trauma that sacrifices the future on the altar of the past.

“They are endangering not only the State of Israel, which I care deeply about and want to exist, but endangering the Jewish population all over the world,” he tells The New York Times . The irony is Gothic: a nation forged from the ashes of genocide now accused of manufacturing a humanitarian catastrophe in its own image.

II. The Machinery of Suffering

The numbers are abstract until they are not:

58,026 dead as of July 13, 2025 .

138,500 wounded in a territory with no functioning hospitals .

67 children dead of malnutrition alone, their bodies “wasting away” in what UNICEF calls a “child survival emergency” .

805 killed while queueing for aid at U.S.-backed distribution points—sites Gaza’s Media Office labels “death traps” .

This is not collateral damage. It is policy. Israel’s blockade has deliberately choked off food, water, and fuel, a tactic Médecins Sans Frontières declares a war crime . When an airstrike kills six children at a water collection point in Nuseirat, the military blames a “technical error” . The munition, they say, fell “dozens of meters from the target.” The children’s names—Seraje Ebrahim, Abdullah Ahmed—go unmentioned in the report .

III. The Theater of Jewish Memory

Patinkin roots his outrage in a specific Jewish ethos. Raised in Chicago’s Jewish community, he absorbed his parents’ refrain: “That’s good for the Jews” or “That’s bad for the Jews” . Netanyahu, he argues, embodies the latter. The actor recalls holding his infant son at a 1980s Soviet Jewry Rally, recoiling from the then-ambassador’s “distasteful vibe” . Decades later, he sees that intuition validated: Netanyahu’s government, he believes, has weaponized Jewish victimhood to justify Palestinian suffering—and in doing so, ignited global antisemitism.

His wife, Kathryn Grody, sharpens the point: “I hate the way some people use antisemitism as a claim for anybody that is critical about a certain policy... Compassion for every person in Gaza is very Jewish” . The couple rejects the “self-hating Jew” caricature, insisting that moral witness is the deepest expression of tribal loyalty .

IV. The Failure of Forgetting

The occupation’s timeline reads like a Greek tragedy:

1967: Israel occupies Gaza.

2007: Blockade begins, turning the strip into an open-air prison.

2023: Hamas’ attack triggers a war of annihilation.

March 18, 2025: Israel breaks a ceasefire with Operation Might and Sword, killing 855 Palestinians in a single night .

Patinkin has long seen the climax coming. In 2020, he narrated a video opposing West Bank annexation, warning it would “formalize an unjust and unequal system” . His critique is not pacifism but preservation: when vengeance becomes a nation’s raison d’être, it forgets how to live.

V. The Aftermath Business

What replaces the revenge business? Patinkin offers no plan—only a plea. He asks Jews worldwide to “spend some time alone and think: Is this acceptable and sustainable?” . The alternatives flicker at the edges of the discourse:

A ceasefire exchanging hostages for Palestinian prisoners .

The two-state solution still nominally endorsed by the UN.

The International Criminal Court’s warrants for Netanyahu and Defense Minister Yoav Gallant .

None seem plausible. Not while children queue for water under drones, and a man in New York watches his 35-year-old film and sees the future buried in the past.

VI. The Inheritance

In the end, Patinkin’s power lies not in his solutions but his symbols. When Inigo Montoya runs his enemy through, he sobs: “I want my father back, you son of a bitch.” . It is the line Patinkin whispered to himself after his own father’s death—a private incantation against loss.

Gaza has no such cinematic catharsis. Only numbers. Only hunger. Only the uncanny spectacle of history repeating itself, with Jews casting Palestinians as the ghosts in their own trauma play. Patinkin’s warning is stark: vengeance is a language that colonizes the soul. Speak it long enough, and you forget how to say anything else.

“The stage is no place for geopolitical grandstanding, and Patinkin’s performance in this arena is one that deserves no applause.”

— Critic in

Perhaps. But when the script is genocide, someone must rewrite the lines.

Share this post